In this contribution, Mariah Ziemer shares how her own work as a visual artist affects her inner world of thought and feeling, therefore shaping her spirituality. Specifically, she explores how drawing helps her process the idea of liminal space and moments of tension.

Mariah studied studio art and theology at Biola University (California, USA) before moving to Scotland, where she is currently an MLitt student in the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts (ITIA) at the University of St Andrews. Besides her TheoArtistry collaboration project with Marjorie, she is currently creating artwork for ITIA’s Transept exhibition and a children’s picture book due for publication later this year.

Sketchbook Stories: Art-Making and the Inner World

If you have watched the film Inside Out, you will recall the memory ‘orbs’ whose colour reflects the emotions experienced within that particular memory. My earliest memory of drawing happens to be an ‘orb’ of solid gold—a joyous occasion, as the film’s animated world would interpret. The scene unfolds like this: When I was about four years old, my parents would roll out long, thin strips of paper across our gridded kitchen floor. They would shower each scroll with crayons, markers, and coloured pencils of all shapes and sizes (a display much like birthday sprinkles on vanilla cream frosting, to my child eyes). Hovering intently over the paper, I would draw here for hours. Indeed, this was my playground.

It is difficult to describe exactly what I drew during those times, but I do recall a sense that somehow, in this space, I had made a friend. As years passed and life introduced more multi-coloured ‘orbs’, I continually returned to this loyal friend whose compassion only seemed to grow with time. Art had become my confidant, a personal reality who would listen without judgment but also unveil my weaknesses, challenge my expectations, and question my deepest convictions.

I cannot speak for every artist, but I think this relationship between artist and craft points to the addictive nature of art-making: Whatever the mode of expression, we recognize its reward as a truth-telling space. I may pick up a pen intending to simply entertain an idea, but along the way, I may discover (whether I willed them to the surface of my conscious or not) the very realities that define and shape who I am. In other words, art-making may help me witness where I am, where I could go, or where I believe I shouldgo; similarly, when my gaze is directed outward to the world, art-making may help me witness avenues of brokenness as well as restoration. This, for me, is how art-making stands as a reflective space and therefore an extension of our inner world. Dwelling here is strange—sometimes terrifying or painful—yet somehow beautiful, somehow right.

Grappling with thresholds

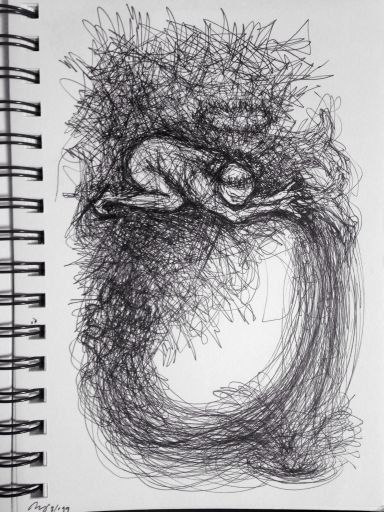

Let’s open up some of the pages in my sketchbook (in all its wonderfully unedited mess!). Recently I have been grappling with the idea of thresholds—the feeling of being on the verge of something, suspended in a liminal space before claiming a belief, deciding to act, and so on. I am also curious what it means to withhold any directional force from this space, as if there were no intentions to move beyond it, one way or another, so only an independent experience or emotion remains. (It is worth noting that bringing this idea to my sketchbook highlights intuition as my guide; unless I am creating for a specific commission, I try to follow the footprints of intuition’s winding path when making decisions before and throughout the drawing.)

For this idea of liminality, I initially did not feel compelled to articulate a specific image or scene. Instead, I wanted to experiment with lines, shapes, textures, marks, and patches of colour to express the cadence of tension and relief, both potentially experienced in moments of waiting. One of the pages contained nothing but aggressive and jagged scribbles; another contained smooth, flowing lines that mimicked the movement of a twirling dancer. My hands moved fast, fast—then slow, slow. I began to think about the transitional spaces between the marks: When does the straight line become a curved line? Or when does the curved line return to a straight one? The word ‘cycle’ popped into my head, and new compositions emerged. Shapes and figures appeared. I drew according to perceptions of positive space, then negative space. I drew clock gears; pedestrians crossing the road or sitting in public spaces; the repeated line of an EKG; imaginary maps without labels; a girl weeping at her bedside—anything that came to mind. Before long, I resonated with moments of tension in my own life, and I began to draw the scenes themselves or more representations thereof. A simple gesture of marks on a page had sparked an entire constellation of images, and it continues to expand.

Reflecting on this particular set of drawings, I want to highlight five observations from my art-making process:

- Some drawings were simply cathartic; the image didn’t arise with a specific purpose, nor did it leave with a shadowed implication—it simply was.

- Conversely, other drawings sparked a chain of pressing (often humbling) questions: ‘How do I respond in moments of tension?’ ‘Why am I frustrated / impatient / happy (etc.) in moments of waiting?’ ‘How is this image an expression of dichotomies, such as suffering and hope?’ Instead of shying away from such inquiries, I challenged myself to lean in and listen to them.

- When extracting images from my imagination, I tried to embrace the spontaneity of my stream of consciousness. Because I was not drawing from observation (an experience heavily catered to sensory perception, which is a different kind of meditation, in my mind), isolating content became more difficult. At times this lack of clarity was frustrating. Other times, I felt relieved to wander in a mysterious space that had no boundaries or the pressures of expectation.

- Contemplating moments of tension in my own life helped me empathize with the idea of another’s. For example, reflecting on pain within my own context helped me recognize its universal qualities but also the weight of subjective reality within its individual manifestations. This thought deeply humbled me.

- My drawings often led me to other forms of expression, primarily poetry. Translating a concept or idea into another medium—where each continually informed the other—occasionally brought insight to a previously blurry idea. Each art form carried the strength of its own voice, but their strength was only amplified when in conversation with the others.

In the end, one of the mysteries of art-making is that it will never fully capture an idea from our inner world. After all, a single doodle lands on an infinite spectrum of expressions (let alone as one of countless visual expressions)—and yet, somehow the making, the act itself, still honours its intended destination. In this sense, by failing to accurately represent the idea, we actually grow closer to it. Our shortcomings can (paradoxically) encourage rather than discourage, propelling us further into the possibilities held within our craft. With great joy, humility, and gratitude, this is how I want to approach my art-making.

What’s more, if my creative endeavours are directed towards a who(rather than simply existing as a what), my art-making stands as a communication device—embodied prayer, if you will. Even as I waver in the threshold of belief or devotion, I can rest assured that my drawing will cry, ‘Lord I believe, help my unbelief’ in ways that my voice could never express.